| Bill of Rights | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Airdate | December 30, 2003 | ||

| Curriculum | Social Studies | ||

Bill of Rights is a BrainPOP Social Studies video that launched on December 30, 2003.

Summary[]

At the intro, Moby makes stuff up and Tim told Moby to not say that about this party.

Appearances[]

Transcript[]

Quiz[]

FYI[]

Quotables[]

] “A bill of rights

“A bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular, and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inferences.” – Thomas Jefferson (pictured), former President of the United States

“The Bill of Rights is a born rebel. It reeks with sedition. In every clause it shakes its fist in the face of constituted authority... it is the one guaranty of human freedom to the American people.” –Frank I. Cobb, American journalist

“The Framers of the Bill of Rights did not purport to ‘create’ rights. Rather, they designed the Bill of Rights to prohibit our Government from infringing rights and liberties presumed to be preexisting.” – William Brennan, former U.S. Supreme Court Justice

“The true [American] revolution was not to defy one earthly power, but to declare principles that stand above every earthly power—the equality of each person before God, and the responsibility of government to secure the rights of all.” – George W. Bush, 43rd President of the United States

Way Back When[]

The American Bill of Rights was influenced in large part by a number of documents asserting the basic rights of individuals—including the 1689 English Bill of Rights and the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights. But perhaps no document was as fundamental in inspiring the Bill of Rights as the Magna Carta.

In 1215, King John I of England was in a dispute with a group of English barons (wealthy landowners) and bishops (high-ranking church officials) over the king’s aggressive tax policy, his mismanagement of foreign wars, and his general abuse of English law. So the barons gathered their wealth and bought a private army, which marched into the capital city of London.

In order to prevent an all-out civil war, King John and the barons met in a meadow called Runnymede on June 15, where John signed a document called the Magna Carta (literally, “great charter”). Once he signed it, the barons re-affirmed their oaths of loyalty to the King.

The Magna Carta’s 63 clauses weren’t designed to give rights to ordinary citizens; they were supposed to benefit only landowning noblemen. Its most important idea was that the king wasn’t above the law and that non-monarchs had rights that the king was bound to respect. And it laid the foundation for all of the legal and constitutional documents that followed it. To learn more, check out our Magna Carta movie!

Laws And Customs[]

The framers of the Constitution were aware that as time went on, their document would need to be changed, altered, and updated every once in a while. That process of changing the Constitution is called amending.

Amending the Constitution isn’t easy, but when an overwhelming majority of legislators believe that it should be changed, it can be done. It requires two-thirds of the members of Congress (both the House of Representatives and the Senate) to vote in favor of a particular amendment. It also requires votes from three-quarters of the 50 state legislatures.

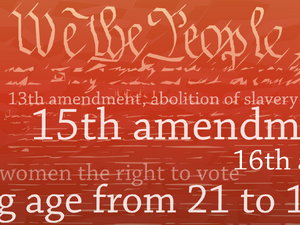

All in all, the Constitution has been amended only 17 times since the Bill of Rights was passed in 1791. Here are some of the important amendments that have been passed:

13th Amendment (1865): Abolishes slavery

15th Amendment (1870): Guarantees African-Americans the right to vote

16th Amendment (1913): Institutes the federal income tax

19th Amendment (1920): Guarantees women the right to vote

22nd Amendment (1951): States that the President may serve a maximum of two terms

26th Amendment (1971): Lowers the voting age from 21 to 18

In Depth[]

One of the most controversial parts of the Constitution is the Second Amendment, which reads: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

The Second Amendment is the part of the Bill of Rights that outlines Americans’ right to own and carry guns. However, many scholars disagree over exactly what the amendment means.

One of the biggest questions surrounds the phrase “a well regulated Militia.” During the War of Independence, which the United States won just a few years before the Bill of Rights was drafted, militias played a key role in the American victory. These were local groups of citizen-soldiers who left their farms, jobs, and homes to fight against England.

But today, militias are pretty much a thing of the past. So the question is whether the Founding Fathers who drafted the Second Amendment intended that the right to bear arms be only in the context of taking arms in a military context.

Some scholars believe that the right to bear arms is an essential civil right, and that if the people were unarmed, they would be at the mercy of the federal government. Others believe that since militias are no longer a part of our society, the Second Amendment isn’t really relevant any longer in that context, and so it should be revised to account for the reality of our time.

It’s a highly debated topic that no one has an answer for right now. What do you think?

FYI Comic[]

Primary Source[]

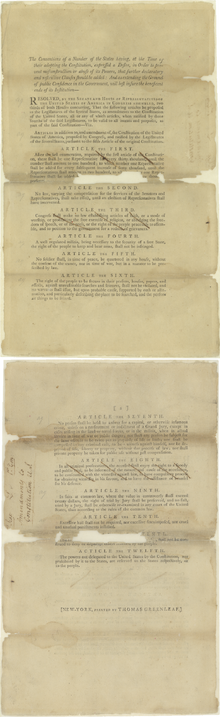

In 1789, Congress approved 12 proposed amendments to the United States Constitution. These amendments were then sent to the states for ratification.

The Conventions of a Number of the States having, at the Time of their adopting the Constitution, expressed a Desire, in Order to prevent misconstruction or abuse of its Powers, that further declaratory and restrictive Clauses should be added: And as extending the Ground of public Confidence in the Government, will best insure the beneficent ends of its Institution—

RESOLVED, by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, two thirds of both Houses concurring, That the following articles be proposed to Legislation of the several States, as amendments to the Constitution of the United States, all or any of which articles, when ratified by three fourths of the said Legislatures, to be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of the said Constitution—Viz.

Articles in addition to, and amendment of, the Constitution of the United States of America, proposed by Congress, and ratified by the Legislatures of the several States, pursuant to the fifth Article of the original Constitution.

ARTICLE the FIRST. After the first enumeration, required by the first article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred; to which number one Representative shall be added for every subsequent increase of forty thousand, until the Representatives shall amount to two hundred, to which number one Representative shall be added [for every subsequent increase of sixty] thousand persons.

ARTICLE the SECOND. No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until and election of Representatives shall have intervened.

ARTICLE the THIRD. Congress shall make no law establishing articles of faith, or a mode of worship, or prohibiting the free exercise of religion, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition to the government for a redress of grievances.

ARTICLE the FOURTH. A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.

ARTICLE the FIFTH. No soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house, without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

ARTICLE the SIXTH. The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

ARTICLE the SEVENTH. No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case, to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.

ARTICLE the EIGHTH. In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation, to be confronted with the witnesses against him, to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favour, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defence.

ARTICLE the NINTH. In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by Jury shall be preserved, and no fact, tried by a Jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

ARTICLE the TENTH. Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

ARTICLE the ELEVENTH. The [enumeration, in the Constitution, of certain rights,] shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

ARTICLE the TWELTH. The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

Proposed Amendments to the U.S. Constitution as Passed by the Senate, 9/14/1789; Bills and Resolutions Originating in the House and Considered in the Senate during the 1st Congress, 1789-1791; Records of the U.S. Senate, 1789-2011, Record Group 46; National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

James Madison, then a member of the House of Representatives, originally proposed 19 amendments. The House passed 17, and the Senate narrowed those down to the 12 listed on this document. The marked lines indicate wording that was later changed before the amendments were finalized and passed by Congress.