| Alexander Hamilton | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Airdate | January 12, 2017 | ||

| Curriculum | Social Studies | ||

Alexander Hamilton is a Brainpop Social Studies episode that launched on January 12, 2017.

Summary[]

Moby is doing a reenactment on Hamilton: An American Musical, and Tim answers a letter about Alexander Hamilton.

At the end, robots put a hat on Tim's head. "I'm not rapping,” Tim says nervously.

Appearances[]

Transcript[]

Quiz[]

Trivia[]

- This episode references the rap-musical Hamilton: An American Musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda.

- Tim does not say what year Alexander Hamilton was born in because it has been not certain yet.

- In the beginning you can see Moby doing the pose Lin-Manuel Miranda does on the star.

FYI[]

Politics[]

In the fall of 1787, the Constitutional Convention submitted a proposal to the American states for a new constitution. Approval by nine of the 13 states was required for it to take effect, and replace the Articles of Confederation. Like some Convention delegates, many Americans feared that the strong federal government outlined in the Constitution would trample individual rights. They voiced their concerns in the press, warning that the new government would be just as tyrannical as the British.

In response, Founding Fathers John Jay, Alexander Hamilton (pictured), and James Madison wrote a series of columns defending a stronger centralized government. Hamilton chose the pen name Publius ("public" in Latin) to represent all three authors. The writings are now known as the Federalist Papers.

Hamilton's essays, which made up the majority, pointed out the failings of the Articles of Confederation. He noted the country's massive foreign debts, the recent tax revolt in Massachusetts, and the terrible state of the economy. He wrote, "We have neither troops, nor treasury, nor government" to remedy the situation. To stop future uprisings, enforce federal laws, and collect taxes, Hamilton argued for a robust federal authority with a national army. But, although passionately written, the essays garnered little public attention outside of New York.

In the centuries since, however, the Federalist Papers have acquired a degree of influence that would have gratified their authors. Several of their ideas have become central to American democracy; among them, judicial review, the authority of the Supreme Court to strike down laws passed by Congress. Though the Constitution does not explicitly grant such power, it is implied in the language defining the Court, which has chosen to exercise it.

Today, the writings of Publius provide invaluable insight into the reasoning and intentions of America's founders. The nation has grown and changed in ways that its architects never could have imagined. But the arguments that inspired the Federalist Papers remain relevant. And the American experiment proceeds the way it began: with passionate debate!

Dollars & Cents[]

Today, money has value because people trust the governments that issue it. But in the 18th century, money need to be backed by specie, the gold and silver in a country's treasury.

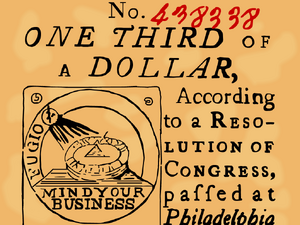

That posed a problem for America in 1776. The newly independent states only had about $12 million total in gold. The war was going to cost far more than that, and Congress didn't have the power to collect taxes. So, instead, it issued paper money that wasn't supported by specie. The currency was known as the Continental dollar, or "Continental," for short.

As expected, people were suspicious of the new money, and many merchants rejected the bills outright. Other vendors simply charged more for customers paying in Continentals. As a result, the currency became almost worthless.

With no workable alternatives, the government responded by simply printing more Continentals. What started as a run of $19 million in bills ballooned to $221 million within a few years. This only further damaged its value. By 1779, it took $40 in Continentals to buy a single dollar's worth of goods! This proved especially hard on soldiers, who were paid in the new currency. According to one popular story, a frustrated George Washington noted that a "wagonload of currency will hardly purchase a wagonload of provisions."

To make things worse, the national and state governments weren't coordinating their finances. Individual states were also issuing bills of credit, I.O.U.s that could be used like paper money. The new nation's economy was in crisis. Congress limped through the final stages of war with Britain, relying on several temporary solutions and an emergency specie loan from France.

When the delegates gathered at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, they had not forgotten the traumatic collapse of the country's first national currency. The federal government acquired new powers, including the right to collect taxes. The newly formed Treasury Department, under Alexander Hamilton, established a central bank and sold government bonds to investors. This stabilized America's money. And the states were no longer allowed to issue bills of credit—that privilege was reserved for the nation.

Ironically, Continentals have experienced something of a comeback since the Revolution. Today, they sell to collectors for hundreds of dollars apiece!

Way Back When[]

Wiiliam McKinley in a 1900 campaign poster

In 1792, Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, pressed Congress into passing the Coinage Act. This established the U.S. Mint, which would issue and regulate American money. It also set the worth of a dollar at 24.1 grams of silver or 1.6 grams of gold. This system was called bimetallism.

A century later, after a series of economic downturns, a debate about U.S. currency erupted. It pitted supporters of bimetallism against those who wanted our money to be backed only by gold. "Silverites" argued that minting silver coins would increase the money supply, helping borrowers pay off their loans. But others, including President William McKinley (pictured, in a recreation of a 1900 campaign poster), argued that an increased money supply meant a decrease in the value of the dollar. That would be unfair to lenders: The money you lent out last year would purchase fewer goods when it was paid back.

Congress chose to abandon silver. It passed the Gold Standard Act of 1900, which set the worth of a dollar strictly at 1.5 grams of gold. The gold standard prevented inflation. But it also restricted the government's ability to set economic policy and respond to financial shocks.

33 years later, at the height of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt nationalized the U.S. gold supply. All privately held gold currency had to be returned to the Federal Reserve. That allowed the government greater flexibility to manage the economic slump. It also helped move the U.S. away from the gold standard.

But it wasn't until 1971 that the link between U.S. currency and the price of gold was officially severed, by President Richard Nixon. Today, the dollar is a fiat currency. That is, it's backed only by public faith in the financial stability of the U.S. government.

Etc.[]

Every year, Congress must pass a budget, outlining what the U.S. government will spend in the coming year. Budgets often hover around $1 trillion! But the government doesn't have that kind of cash just lying around. It needs to borrow it!

The U.S. borrows money by selling bonds and other securities. Some bonds entitle buyers to regular interest payments. Every year, the government pays bondholders hundreds of billions of dollars in interest! It’s paid by selling even more bonds. This scenario has the potential to lead to an endless spiral of debt.

But there's a catch: A 1917 law limits how much the government can borrow. This limit is known as the debt ceiling. Once public debt reaches that point, the government can't borrow any more until Congress agrees to raise the limit.

If Congress were to refuse, the government would suddenly find itself without the money to run its programs, from disaster relief to veterans' benefits and Social Security. It also wouldn't be able to make its interest payments. In other words, the country would default on its loans. This likely would ignite a worldwide financial crisis!

For decades, Congress raised the debt ceiling without much fuss. After all, doing so paid for spending it had already approved. Plus, the alternative was terrifying. But, in 2010, some elected representatives vowed to take drastic measures to lower government spending. For the next four years, these members of the Republican Party announced that they would not raise the debt ceiling unless their demands were met.

To date, disaster has been narrowly averted. Deals have been struck with moments to spare, preventing international fallout of a U.S. debt default. But the willingness of certain legislators to hold the global economy hostage for political ends has had consequences. It has damaged the country's creditworthiness, its ability to borrow money. In 2011, a debt rating agency downgraded U.S. bonds one notch. In other words, its view was that America was slightly more likely to default on its debts. If more downgrades occur, the government will need to pay higher interest rates on its bonds, which will negatively affect all Americans.

The money we spend derives its value from trust in the government that issues it. The modern economy rests on a similar leap of faith. Threatening to break that contract is dangerous stuff. Economists fear the effects of future debt ceiling stand-offs. As debt limits are reached more and more frequently, there are more and more opportunities for legislators to play chicken with global financial collapse.

In Depth[]

When the U.S. government wants to borrow money, it issues Treasury securities, also known as bonds. Here's a look at a few of the most common types.

Savings Bonds: These are the simplest Treasury securities, which you can buy from most banks. Series EE bonds can be bought for half their face value. For example, you might buy a $50 bond for $25. It takes 20 years to mature, or reach its full value, at which point you can redeem it for $50. Or you can wait longer, since it's guaranteed to continue earning interest for 30 years. Series I bonds can be bought for their full face value. You can cash them in after one year for the amount you paid, but they also continue earning interest for 30 years.

Treasury Bills: T-bills are short-term securities. You buy them for less than face value, and then wait just a few days or months until they mature. Then you can cash them in for their full value. Or you can sell them before they mature. For example, you could buy a $50 T-bill with a one-year term for $45. In one year, when the bill matures, you would earn $5 in interest. Or, sell it in six months and earn less than the full $5.

Treasury Notes: The price of a T-note is set at an auction, so it might be lower, the same, or higher than the face value of the security. T-notes are short- to medium-term investments, maturing anywhere between two and 10 years after you buy them. While you own one, the government pays you interest every six months until the note matures. As with any security, you can sell it before it matures.

Treasury Bonds: These are long-term investments; they take 10 years or more to mature. Like T-notes, their price is set at auction. You receive interest from the government every six months, and you can cash them in for their full face value at the end of their term.

In Practice[]

The Electoral College is a complicated way to select a President. Why not let citizens choose their Commander-in-Chief directly? The answer goes back to 1787, when representatives from around the country were hammering out the U.S. Constitution.

The election process was one of the most hotly contested issues of the Constitutional Convention. Some delegates thought Congress should pick the President. They feared that citizens of the young nation couldn't be trusted to make informed decisions. Others argued that this approach would lead to an executive branch that was beholden to the legislature.

There was another sticking point. The South didn't want northern states to have more power just because they had more voters. To avoid alienating slave states, the Convention settled on the Electoral College. Southern states would be allowed to count three-fifths of the slaves within their borders toward representation, in Congress, and with presidential electors.

This compromise shifted the advantage to southern states—in effect, rewarding them for slavery. In 1800, Virginian slave-owner Thomas Jefferson won the presidency over Massachusetts's John Adams. Jefferson's margin of victory was due to the extra votes granted to southern states for their slave populations. Of course, those slaves were not allowed to vote, which meant each vote from a Southern state was worth more than one from a Northern state.

While the end of slavery also ended the shameful Three-Fifths Compromise, its legacy remains powerful. The Electoral College still privileges some states over others—rural ones, in particular. Why? Well, each state's elector number matches its number of representatives in Congress. That means the minimum elector number is three: because each state must get at least one representative in the House of Representatives, and two Senators. As a result, states with very low populations are over-represented.

Here's a real-life example: Wyoming, with about 600,000 residents, has three electoral votes. California, with over 39 million inhabitants, has 55 electoral votes. That sounds like a lot, but it isn't proportional. In presidential elections, each Wyoming vote counts 3.6 times as much as each California vote!

The controversial 2000 election threw this reality into stark relief. Democrat Al Gore won the votes of a majority of Americans, only to lose the Electoral College to Republican George W. Bush. The backlash reignited the centuries-old debate. And that was nothing compared to the outrage inspired by the 2016 election: Democrat Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by almost 3 million votes, but lost the presidency to Republican Donald Trump by 74 electors!

Some critics say we should end the Electoral College system. They believe a direct election by the people is more in line with America’s democratic principles. But changing the election system would take a constitutional amendment and numerous changes to local and national voting laws. So, at least for now, we're stuck with the Electoral College!

FYI Comic[]